The following article has been submitted by Lucy Berry, studying at Swansea university:

Johnes, Martin (2015). Archives and historians of sport. International Journal of the History of Sport 32.15 (2015), pp. 1784-1798.

- Material from individuals whose lives centred on sport are rare, perhaps because most individuals in sport do not think to deposit their material in archives, whether because of ignorance, modesty or secrecy (p. 1788).

- However, there are some examples, as Johnes notes; A flavour of such collections can be gained from the catalogue description for the six boxes of material at Glamorgan Archives relating to the rugby international, commentator and journalist Bleddyn Williams (1923-2009). P1788).

Much of the value of archival sources comes from their entirety rather than any specific document within a collection. Aside from Swansea R.F.C., Johnes notes the detailed records of Severn Sisters RFC. Although the club was relatively small and not one of Wales’ rugby elite, its accounts and minutes show the complexity of running a rugby club, and how committee business in this amateur sport was dominated by organising travel, insurance and raising money to cover the expenses (p. 1795).

- In comparison to Swansea in the 1930s, the documents give the sense of a club that was clearly run on a sound and responsible basis and which saw itself as part of a rugby community (p. 1795).

|

| St Helen’s Ground in 1929 (Aerofilms) |

|

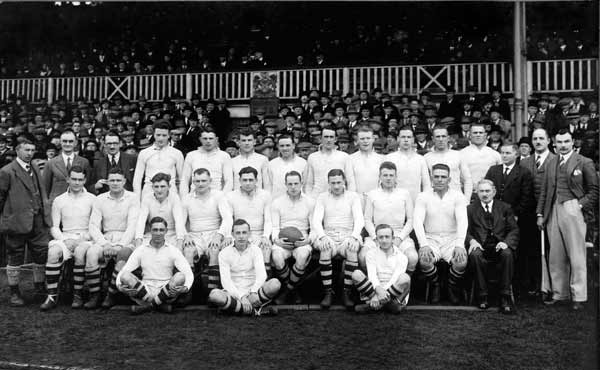

| Swansea RFC 1st XV 1929-30 – P 40, W 29, D 3, L 8. |

David Farmer, The Life and Times of Swansea R.F.C. The All Whites

Ch 14. The ‘Public Schoolboys’

- ‘Pendragon’ was of the opinion that the season of 1930/31 had been ‘one of the worst on record’ (p. 160). Seventeen games had been lost, and, for a variety of reasons, the club had struggled to find a settled side.

- During the season 45 players had appeared in the white shirt, including several 17-year olds. In his end of season analysis, the Post man, whilst searching for something positive to say, could only ponder on the root cause of the club’s problems. He wrote that:

‘Thirty years ago, Swansea was the most successful club side in the world… even when it is allowed that the game has changed since those days, it has to be confessed that the “All Whites” have neither maintained the old standards nor advanced with the times.’

- In searching for reasons as to why the club had hit such a downfall, there was a hint of despair in the writing of journalists:

‘Opportunities for practice were not so numerous as they used to be, there were smaller crowds and less enthusiasm.’

- Furthermore, and this seemed to be a corner-stone of ‘Pendragon’s’ argument, unlike their artisan predecessors, the new breed of player, ‘the Public Schoolboys’, could not be relied upon to stay with the club. He concluded his analysis with the thought that ‘the present season has been a mixture of satisfaction and depression… a period of never-ending experiment.’

- On reading these words, there was no doubt that any member of the beleaguered British Government of the time, would have been able to nod perceptively in agreement, as he considered them in the light of the nation’s economy.

As far as the ‘Whites’ season was concerned, one can understand at this distance the loyal scribe’s concern. The man had grown up with the fact of a Swansea team which was a collective living legend. His lot was to report on the doings of what he saw as mere mortals.

- Statistically, however, the club had not been at its worst in the era that perturbed ‘Pendragon’; at the end of three other seasons during this period, more games had been lost, including two campaigns during which opponents won a score of games.

- Furthermore, there were positive aspects to be considered. Some exceptional talent had been unearthed, with the University club providing players of the calibre of Watcyn Thomas, Claude Davey and Idwal Rees, while Dai Thomas was regarded in ‘high quarters’ as one of the best all-round forwards in the country’. Furthermore, there was the talent of Jim Sullivan a Cardiff player at the time (see record below: source, Robert Gate, Gone North, p. 38).

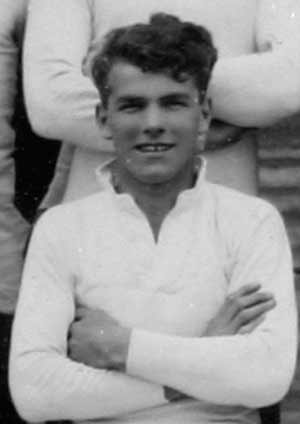

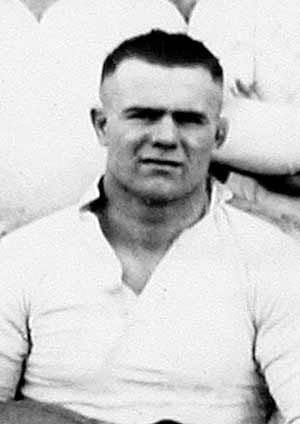

|

|

|

|

| Watcyn Thomas | Claude Davey | Idwal Rees | Dai Thomas |

- There were unexpected victories too over Bristol, and Gloucester, and, in April, over a Cardiff team ‘packed with internationals’, who were ‘swamped in all phases’ by an experimental Swansea side in which three of the backs were under eighteen (p. 160).

Despite this, Farmer states how ‘the reality of the economic situation at the start of the third decade of the century was hardly conductive to outright optimism’ (p. 161).

- For that reason, the point which the journalist made about ‘public school boys’ was particularly valid.

- It was probable rather than possible that once a university man graduated, he would leave Swansea to follow his career. Conversely the likes of Fred Scrine and Dick Jones, both of whom were stonemasons and Ivor Morgan, who was a coal trimmer, followed their trade in the old borough.

- In due course, as if to prove the point, Watcyn Thomas took a post in St. Helen’s, Lancashire, whilst Claude Davey moved to the Midlands. Meanwhile, the artisans in the club were still being tempted by the ‘Northern Poachers’, and soccer was increasing in popularity in the town, thus diverting potential rugby talent and support to the round ball game.

There was a slightly better outcome for the team in the 1931/32 season. In contrast to their form during the previous season, the ‘All Whites’ started the 1931-32 campaign with a flourish:

- By the end of September, the team’s record read something like that of Gordon’s ‘Invincibles’. (The “Invincibles” were the 1904-05 side (Played 31, Won 27, Drawn 4, Lost 0). It was the culmination of a period when they were Welsh Champions 6 season out of 7 from 1898-99 to 1904-05 and were runners up in 1902-03. Skipper Frank Gordon was nicknamed “Genny” Gordon after general Gordon of Khartoum).They had played six games, won them all, and their points record stood at 113 for, 41 against (p. 161).

- Eyebrows were raised in Swansea, for there had been no indication during the close season that such a start would be made. Yet, before each season starts, hope beats eternal in the hearts of the supporters of a rugby club; those who followed Swansea were no different from any others.

Prior to the start of this successful campaign, the hope of what would be was clouded by a great deal of controversy.

- It was reported that the club’s financial committee had ‘stirred up a hornets nest’ by arranging for a resolution to be put to the AGM to disband the Second XV. This was argued as necessary to do due to ‘the need for an economy campaign’. This was the economic climate in which Swansea and other clubs had to function during the Great Depression.

- Opponents of the proposal were heated. Their position was summed up by a spokesman who stated, ‘if this measure is enacted then the status of the club will be affected.’

- The ‘opposers’ carried the day, and the finance committee was obliged to look elsewhere for savings due to this.

The Springboks (p. 162).

Since the team were doing so well, there were those who argued that the winning side should be retained en bloc to oppose the visiting South Africans. There were disagreements as to which of the players should be called upon to oppose the tourists; famous ‘outsiders’ were favoured; Claude Davey, Watcyn Thomas and D.P. Manley (former Swansea players at this stage).

|

| D P Manley |

- The arguments about retaining team spirit, giving the existing team members their chance, and it being unfair to drop players for the big day when they had done so well in early games, fell on deaf ears.

- In the event, the temptation to include the ‘stars’ was too great. Whether the ‘Whites’ would have done better if a different decision had been taken can only be a matter of assumption.

- However, it is possible to argue that, in the long run, it might have been better for the club if the ‘normal’ side had been selected.

Despite this, on the day, 40,000 people (said to be a Swansea club record) packed St. Helen’s for the game, thus giving the unstated approval, at least, of the supporters to the selection of Davey and the others (p. 162).

The match against the Springboks was lost 3 – 10, two missed tackles just before half-time proving costly. As the South Africans defended their lead in the second-half, Swansea came back into the game and Claude Davey scored a wonderful try just before the final whistle. Davey, along with Tom Day, Watcyn Thomas and Will Davies all played for Wales against the South Africans as well.

The next visitors to St. Helen’s were Neath. Given that their favourites had done so well in domestic football and had run the tourists so close, Swansea supporters viewed the game against their neighbours with some confidence- 9,000 supporters were said to be at the St. Helen’s ground for the game (p. 163).

- Despite this, it was Swansea supporters who left the ground disappointed, as Neath had taken the club’s unbeaten record ‘on the break’.

- Furthermore, the Neath side had included W.J. Trew junior, who had moved to the Gnoll club during the close season, meaning that the defeat was doubly hard to take.

|

| Billy Trew Junior |

In December of that year, the winning run for Swansea was once again interrupted. The ‘Whites’ were beaten away from home for the first time that season, Bridgend being the victors.

- Accident?

- The next match would answer that question; Llanelli visited St. Helen’s having previously beaten the men in white on four out of 5 occasions (p. 163).

- Given the importance of the game the selectors had hoped to include Watcyn Thomas and Idwal Rees, both of whom were home for Christmas, but neither were available for the game (p. 164).

- Even so, honours finished even.

1933/34

1933-1934 was one of the worst seasons for Swansea Rugby. Due to the economic recession and high levels of unemployment, players were going north to play Rugby League, with families to feed and jobs far and few, players were tempted with a lump sum of perhaps £200 plus and a regular job and win bonus!

|

|

| Watcyn Thomas’ Welsh jersey v England 1933 | Idwal Rees’ Welsh jersey v Ireland 1933 |

There were several players who left the team during this period to play elsewhere (see below).

- With unemployment a continuing problem the attitude of Swansea supporters to further incursions from the Rugby League was now fatalistic. Most families had one or more of their number without work, and, consequently they could understand the lure of the north (p. 166).

- Lump-sum payments were appealing, but the real attraction was the guaranteed job (p. 166-67).

Nevertheless, the club was less than enamoured. It was Broughton Rangers once again who darkened the doors of St. Helen’s. They had been instrumental in luring the famous James brothers David and Evan away from Swansea in the 1890s. (p. 167).

- Reggie Bateman was the player involved this time, and to cross the line he took £250, a match fee arrangement and a job. He told the press that, had he been offered a job in Swansea he would have remained an amateur.

Furthermore, there was a great problem of drought for the club following a severe lack of rain, which in turn affected Swansea’s water supply. There was something of a drought, too, regarding winning Swansea performances.

- For example, in early October, Llanelli held the upper hand throughout the game and beat the homesters for the third time in succession. Such were the expectations of the press at this stage in the campaign that it was reported that ‘there was some consolation that the deficit was as small as it was’ (p. 167).

- A fortnight later, when it was announced that Billy Trew junior was also going north, the Swansea club and its supporters were downcast. Even the strongest club would have reeled at losing four senior players in such a short time.

- The fifth to depart for Rugby League was Norman Pugh. He had been recommended to the Whites by Swansea and Wales hooker, J.H. John who said that Pugh (of Ystalyfera) was the best second-class player in Wales. He joined Oldham RL and played an incredible 363 games in the Second Row up to 1948. He gained 6 Welsh Rugby League Caps.

- Another mid-season departure was Loughor product Gordon Deeley who went to Hull Kingston Rovers where he played 36 games on the wing and scored 6 tries.

- Soon to follow was W.G. Benyon who got in the First Team as a Hooker. He got a job in Bristol and joined the Bristol Club. Later in the season he played well for Bristol against the Whites. This product of Penclawdd and Swansea University was a great loss.

- Following this, Dudley Folland and Wilf Harris departed. They decided to play football rather than rugby. Folland got into the Swansea Town Reserves team, while Harris soon returned to rugby. He played brilliantly two seasons later in the win over New Zealand.

- Despite Swansea losing some of its best players, this was not the only case; all the top clubs and the Welsh team were affected as they too lost players.

|

|

| Dudley Folland | Wilf Harris |

Even so, in Swansea’s case, the blows were even more damaging. ‘Rover’, in attempting to analyse the position in which Welsh rugby found itself at the time, expressed understanding of the action of players who ‘went north’. He castigated the Welsh Union for not doing more to alleviate the problem and argued that ‘Rugby should provide a career for its top performers’.

- He added that many south Welsh clubs were ‘steeped in debt’, and every one of them would have to ‘put its house in order and its methods would have to be modernised’. Furthermore, those who administered Swansea Football Club were no different. For example, ‘Pendragon’ argued that ‘they should pay more attention to the welfare of their players’.

– Ronnie Morris, he pointed out, had been ‘capped’ at outside-half and, in the following game for Swansea the selectors had moved him to centre. The scribe felt that Morris was being ‘messed about’.

– Furthermore, as far as Billy Trew junior was concerned, ‘Pendragon’ believed that the great Billy Trew Senior would have ‘given his son his benediction’ about going North.

In November of 1933 there was fresh controversy in Welsh rugby. The Welsh Union was to erect a ‘colossal stand at Cardiff Arm’s Park’ (p. 168)

- ‘Pendragon’ and, clearly, those who administered the sport in the west, read more into the development than might have been apparent. ‘Judging by the portents, the members of the Welsh Union are concentrating on the centralisation of international games at Cardiff. This is a sad blow for the west.’

- Despite Llanelli’s initiative in calling a meeting of west Wales clubs to protest, the easterners were continuing to drive in the wedge designed to result in an eastern monopoly.

In December of the same year, almost as if the ‘Whites’ had not had enough problems to deal with, there was a further defection. This time it was W.G. Benyon, who left Swansea for a job in Bristol.

- Despite this, at Christmas time the Post could report an old-style victory at St. Helen’s.

- With Claude Davey (home on holiday) in the side, and Bryn Evans back from Penclawdd, the ‘Whites’ indulged in an ‘orgy of scoring’.

- Idwal Rees was the dominant figure in a match which was recorded as the biggest defeat handed out to the ‘Exiles’ by the Swansea club (pp. 168-69).

However, hardly had the smiles settled on Swansea faces than there were two further defections following this success (p. 169). Dudley Folland signed for Swansea Town A.F.C., and Wilfred Harris also said that he was interested in changing codes.

1935-36

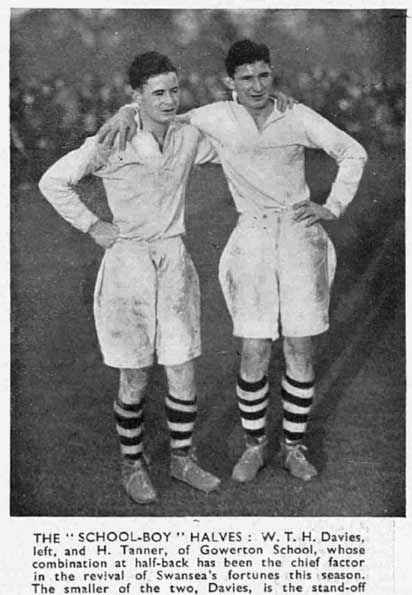

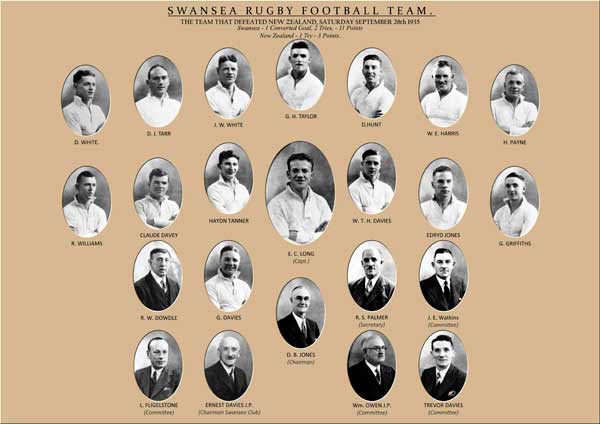

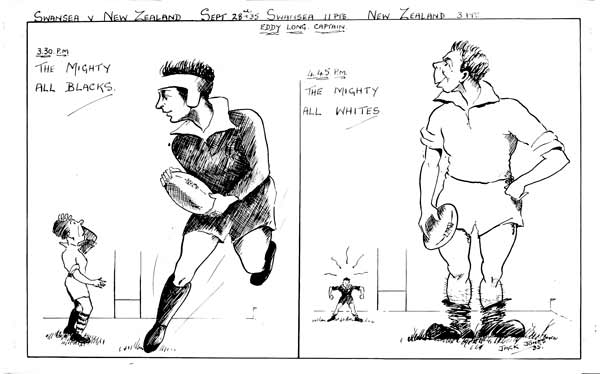

- Given that the club had found another pair of half-black gods, there was a degree of optimism among Swansea supporters as the season approached (Willie Davies and Haydn Tanner, both of Gowerton School, were still just 18 years old when they played for Swansea against New Zealand in September 1935).(p. 173).

- Together with players like Edryd Jones, Harry Payne and D.J. Tarr, the ‘Schoolboys’ were thought to represent the nucleus of a fine side.

- On the famous day that the ‘Whites’ beat the All-Blacks, the ‘Whites’ had won a hard-fought match 11- 3 as a result of effective all-round play. The side showed superb spirit, brilliance at half-back, tenacity, combination and purpose in the pack, and magnificent defensive and offensive play, particularly by Claude Davey in the centre (p. 174).

|

|

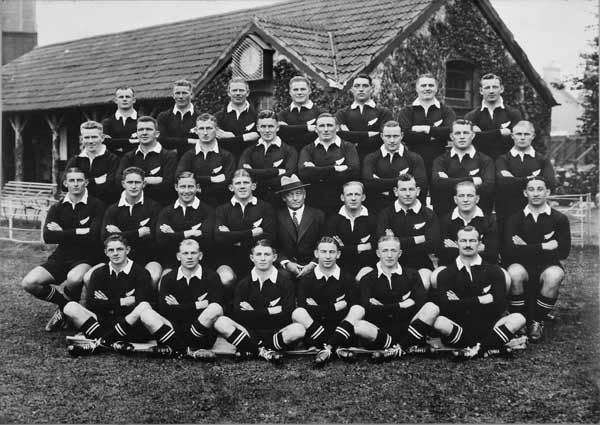

| The Swansea team that beat New Zealand on 28th September 1935. | A Jack Jones cartoon depicting the great victory |

|

|

| The All Blacks squad of 1935-36 | |

However, following this success, by mid-April, the team’s performances gave great cause for concern. The scribe was discussing ‘Swansea’s problems’. The burden of his argument was that the fixture list congestion had resulted in the club having to play as many as three games a week, whilst injuries, absence, staleness and selectorial whims had also taken their toll (p. 177).

- The end of the season coincided with a government announcement that income tax was to be increased (up 3d at once) in order to pay for defence costs.

- As far as Swansea R.F.C. was concerned, the ‘cost’ of its loss of form in the final quarter of the campaign had been that it had forfeited its place at the head of the unofficial Welsh table (p. 177-78).

– Even though ‘Pendragon’ had stated that he did not like this arrangement, the discerning reader of his comments in his season’s summary was would have noted the implication that he would have been delighted that the ‘Whites’ maintained their ‘senior position’ (p. 178).

– Furthermore, ‘Pendragon’ found many positive points to raise despite the disappointment of the previous season. Edgar Long, ‘light-haired son of Mumbles’, had a particularly good term of office; Harry Payne had been a ‘consistent scrummager without pretensions’, whilst Ronnie Williams, Joe White and George Taylor had all made valuable contributions during the season.

- There was some excellent news about Tanner- University College, Cardiff had offered him a place for the following term.

1936-37

- Defeated by Neath following success at Bristol; Davies was unavailable for the Neath game, thus meaning Neath won by scoring the only try of the match (p. 178).

– Defeat made worse given that the try-scorer for Neath was an ex ‘All-White’, Harold Powell.

The performance on the field that day in Neath apparently ‘left a great deal to be desired’; however, the next fixture showed something of the potential of the Swansea team.

- Swansea beat Cross Keys, who had won the unofficial title at the end of the previous campaign, 24 points to 8, and had opened in ‘a most amazing fashion with two quick scores’ (p. 178).

- Following on from this, Swansea also beat Llanelli 8-3, which was the first victory over the Scarlets since 1932. In the process, Llanelli lost its unbeaten record, despite the fact that Tanner was injured for the majority of the game.

Another unbeaten record was claimed the following Saturday when the English club, Richmond, were well beaten (p. 178-9).

- 15-8 (according to the Western Mail), ‘hardly reflected Swansea’s superiority’ (p. 179).

- Captain Ronnie Williams (with Swansea University connections) ‘led by magnificent example).

- Pendragon wrote that ‘a few more [wins] of that variety will bring back the crowds’.

However, following this, it was evident that the ‘All Whites’ had sadly returned to their previous form. In a fiercely fought match against Llanelli at St. Helen’s, the Post reported that ‘many discreditable happenings took place’.

- What was reported as an ‘unpalatable climax’ resulted in a player from each side being sent off.

- Swansea and Llanelli spokesmen made a joint statement after the match to the effect that the remaining two games of the season, and all those scheduled for 1937-38 would now not take place (p. 179).

On the last Saturday of 1936 there was joy for Swansea followers as, with Idwal Rees in the side, the ‘Whites’ gave a ‘gratifying performance’ to beat London Welsh- scoring 21 points without reply (p. 180).

Following this, Pendragon sought for reasons which might explain the inconsistency of the side (p. 181).

- Among other things he restated his continuing criticism that the club had never put out a settled side.

- Part of that problem, he argued, could be put down to the fact that the club had to rely on university players. He pointed out that these men were obliged to turn out for the University and, in some cases for invitation XV’s.

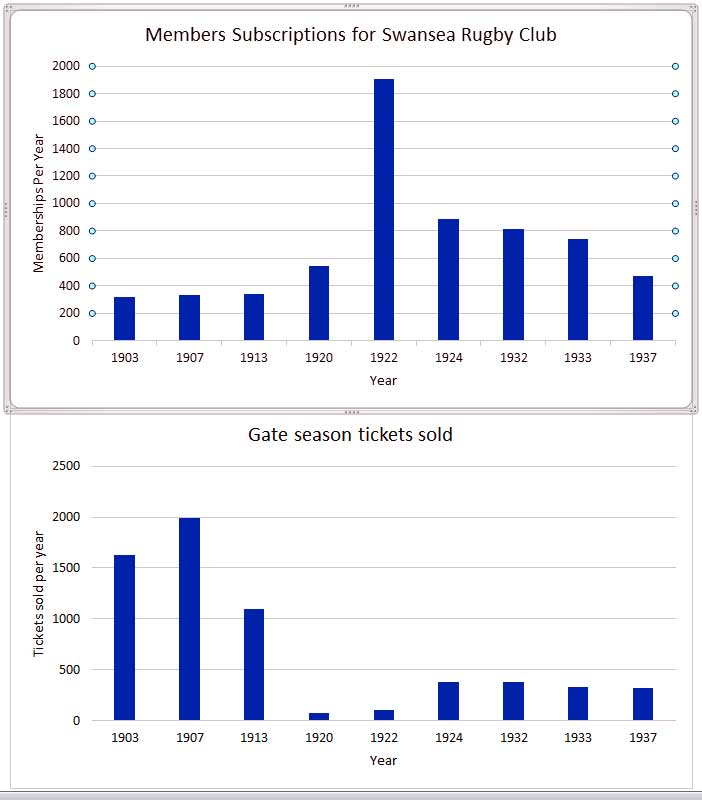

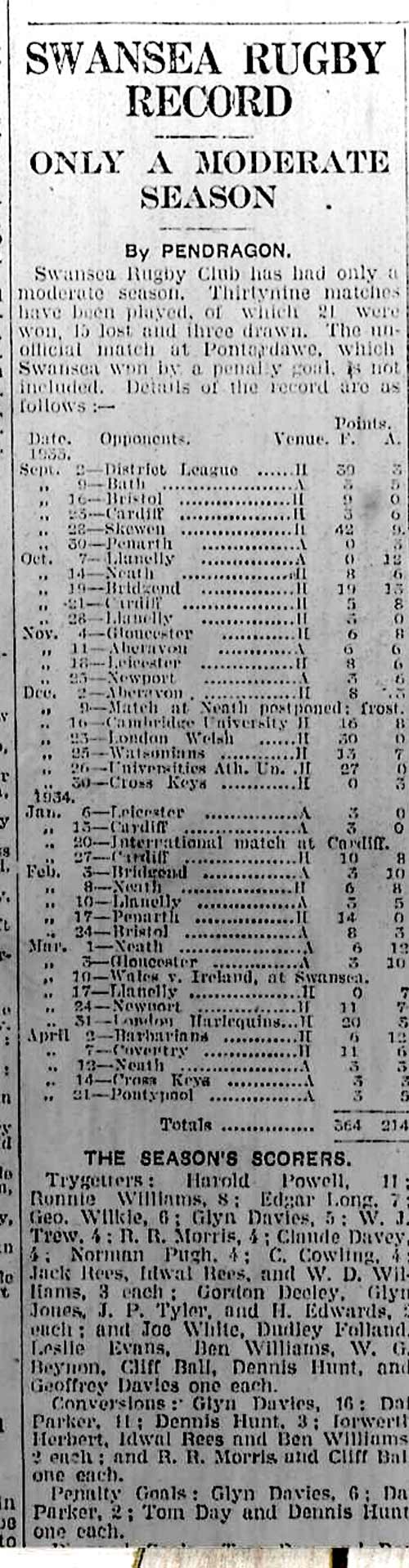

Below: a graph showing the rise and dramatic fall following 1922 with regards to the members subscriptions of Swansea R.F.C., the annual amount of gate season tickets sold and a newspaper article detailing the games won and lost in the club’s worst season by Pendragon. The data for the graphs are drawn from Swansea RFC archive records.

|

| Pendragon’s round up for the 1933-34 season (South Wales Daily Post) |

Fields of Praise notes

- In 1936 a cluster of Welshman requested Welsh Rugby Union aid for their all-Welsh rugby team. The Union was finding it difficult to sustain those clubs left in Wales, many of which were closing abruptly as the pits and steelworks which had once spawned them (p. 293).

- Taibach was forced to close in 1937, along with the Nelson club, in the wake of Taff Merthyr and Nine-Mile Point collieries disputes which saw the imprisonment of several club stalwarts (p. 294).

- Rugby Union hardly exercised an exclusive influence on the sporting public of South Wales in the late thirties, as this was a great era in the history of Welsh soccer (p. 297).

- The signing of Merthyr’s Bryn Jones by Arsenal in 1938 for a record fee of £14,000 was emblematic of the hold that association, more than rugby, held on the eastern valleys of Glamorgan at this time.

- Rugby had lost the momentum which the revitalised back play of 1931-36 had generated. International occasions accumulated a full house of supporters, but club rugby languished. The 18,000 Welshmen who went to Murrayfield in 19383 were more than double the aggregate of spectators who watched first-class rugby on an average Saturday. On 13th December 1937, the soccer and rugby clubs of Cardiff, Newport and Swansea all played at home. The rugby games attracted 7,000, whereas the soccer 44,000 (p. 297).

- The quality of football provided by super-fit servicemen was of a higher order than the drab and frequently over-vigorous matches that predominantly in club rugby in the second half of the pre-war decade (p. 298).